“The thing about Mumbai is you go five yards and all of human existence is revealed. It's an incredible cavalcade of life, and I love that”

– Julian Sands.

It’s an alien feeling to be

on a motorbike trip, but not to be excited about the prospect of getting back

on the road after a couple of days break from riding. As we left Anjuna Beach

and rode slowly out of town, I didn’t have the same buzz that I’d usually have,

the anticipation of what we’d discover next. Instead I was wondering how awful

the roads would be that day, how many aggressive people we would encounter, how

many times I’d have to fend off someone I’d offended simply by being on the

road, would we even make it in one piece? I needn’t have worried though, for

the first time in several weeks we were to have a very good day’s ride.

Given our two month visa

restraint, we realised we needed to start making some progress north and so we decided to head for Mumbai. We’d heard a lot of negative things about the

city and we’d discussed whether we’d perhaps be better off finding a place to

stay outside the city and then catching a train in, but we quickly dismissed this idea. If we could ride through Mexico City, Guatemala City, Hanoi, San

Pedro Sula, then surely Mumbai couldn’t possibly be any worse.

We rejoined national highway

66, a road that had caused us some significant grief during our last few days

of riding on it, but heading into Maharashtra state drivers seemed to relax a little

and we found far fewer people deliberately aiming for us. Cars backed off a

little and allowed us the space to overtake if we were next in line rather than

blasting through with a villainous cackle and running us off the road. For the

first time I started to enjoy riding in India. We were too far from Mumbai to

complete the journey in one day, it would take closer to three, so we decided to

head out to the coast again and turned off on to highway 4.

As soon as we left the main

road the scenery changed completely and we found ourselves riding across open,

sweeping plains, through fields of deep golden coloured grasses and not another

vehicle in sight. We reached Ratnagiri, a small town on the coast, but it was

only late afternoon and we still had at least a couple of daylight

hours. Feeling newly energisied from a pleasant day’s ride, we decided to

continue. A little further up the coast it appeared that there was a ferry

bridging the gap in the road that would allow us to continue up along the

coast. A quick check on Agoda showed a hotel right next to the ferry dock on

this side and another the other side, so we decided to continue and see if the ferry

was still running that late in the afternoon. If it was we would cross and stop

just the other side, if not we would stay at the hotel on this side and catch

the ferry in the morning.

Leaving Ratnagiri the road

climbed steeply, following the cliffs at the very edge of the water. Below us

some of the most beautiful, deserted beaches I’ve ever seen stretched out into

the Arabian Sea. What little other traffic we met was courteous and quiet,

obviously also soaking up the calming effects of the stunning scenery we were

passing through. We arrived at the ferry dock at around 5.30pm, a tiny concrete

slip at the end of a series of winding country lanes, and were pleased to find

that there was indeed a ferry leaving in half an hour. Whilst waiting we

sampled some very good Bhelpuri from a vendor by the ticket office and watched

the fishermen unloading their catch of prawns into tuk tuk trucks which

strained under the weight of their load as they crawled up the slip, using

every scrap of power they had.

Shortly after the ferry arrived and we rode on.

Halfway across we decided it would be a good idea to check that the hotel we

were heading for had a room for us. It was then, as we watched the sun touch the

horizon that we discovered that the place we had been looking at wasn’t

actually near the ferry dock at all, it was another 90 minutes ride.

The first part of the ride wasn’t so bad. The twilight granted us enough visibility to negotiate the gritty, winding lanes away from the river. As is always the case when we are caught riding in the dark, the road quickly deteriorated and we spent the next hour bouncing in and out of potholes and over rogue speedbumps in the dark, hoping that we wouldn’t find loose grit on corners. In daylight it would have been a perfectly nice ride, but in the dark, tired after a long days ride and with the added danger of sleeping cows, it wasn’t my idea of fun.

We reached the village where the guesthouse was located, after a final push up a steep, gravelly track dotted with boulders, reminiscent of our nighttime ride in Nicaragua. As soon as we turned on to it Evan took off ahead of me, obviously keen to avoid a repeat of that episode. The guesthouse took some finding, but find it we did and after a very nice chicken curry dinner cooked for us by our host, we retired to bed.

Leaving there the next day

we headed a little further north on the same route, taking another

road-replacement ferry before deciding that we really were adding unnecessary

miles to our journey and headed back to the main road in an attempt to make up

some time. In hindsight this might not have been such a good decision as we

soon rejoined all the other assholes on the road, fighting our way into Navi

Mumbai through roadworks in rush hour traffic. We regularly got separated in

the craziness and at one point I got into a fight with the driver of a battered

Suzuki who took offence at me passing him while he was stuck in the queue.

Nevermind the fact that a dozen other bikes also passed him, all ridden by

local men, it seemed that I was the only one he deliberately aimed his car at

before shouting out his window at me ‘Why don’t you just fuck off, go somewhere

else?’ It seemed a little unnecessary. As he passed me about ten minutes later

he took another swipe, this time pushing me off the road into the gravel ditch,

much to his satisfaction.

Realising that Mumbai proper

was still a bit too far for that day and by now covered in a thick grime from the relentless exhaust fumes, we stopped at a very unfriendly hotel in

the new city, run by the most robotic, disinterested staff we’ve encountered so

far. The only person who smiled or showed any enthusiasm for us being there was

a young porter who did his best to chat with us in broken English, advising us

to ensure we locked our bikes up and then carried my bag up to our room for me.

Usually I refuse this kind of help, partly because I don’t need to be waited on

and can very easily carry my own bag, and partly because tipping people for

doing this soon adds up, but on this occasion I felt like his friendly approach

deserved to be recognised and I tipped him generously. Not liking the look of the

hotels food offerings and reluctant to give them any more money that was

absolutely necessary, we wandered down the road to a google recommended

restaurant for what turned out to be some very good food.

The restaurant

experience is another thing that has taken some getting used to in India. I’ve

talked previously about the lack of personal space, the fact that people invade

it all the time, and restaurants are one of the worst places for this. Many

times we’ve been mid-bite and random people will come and sit down at our

table, or even worse, hover over us, demanding to know who we are, where we are

from and can they please have a selfie?

As soon as you enter a

restaurant you are handed one menu. Two people, but always only one menu. The

waiter them poises his pen above his order pad and fixes you with an intense

stare. No time to browse the offerings, he wants an answer immediately. Clearly

you are supposed to know exactly what you want before you even know what they

have. Attempting to send them away sometimes works, sometimes not. At this

point we have the tiresome ‘not spicy’ conversation, knowing full well that

whatever they bring will be spicy enough to strip the skin off the roof of your

mouth regardless of your request.

When the food is served, it is indeed

‘served’. If you order rice and curry for example, the waiter, despite your

protestations, will try their best to dish the rice on to your plate and will

then pour your curry over the top of it. It frustrates the hell out of me,

because I prefer to put things on my plate where I want them. It’s the same

with drinks. In some places they’ll pour the initial glass, in others they’ll

take it one step further and refill your glass every time it’s less than half

full. If this means reaching across the table over your food as you try to eat

then so be it. They’ll also decide it’s time to refill the cutlery or napkin

holder or condiments mid-meal too. It's infuriating and there’s a

strong urge to say something about it, but then you realise that it’s the norm

here. There just is no concept of personal space.

The following morning, back

in our miserable hotel room we were woken by what sounded very much like a

smoke alarm going off. It stopped, we ignored it. A minute later it went again.

We ignored it again. Then it again. This time I pulled on some clothes and

opened the door. Stood outside was an expressionless room boy with a tray

containing a plate of cold rice and four slices of stale bread. Not content at

just passing me the tray, he pushed past me into the room, tutted when there

was no clear surface for him to deliver his breakfast offering and shoved all our

stuff unceremoniously on to the floor so he could set the tray down. Now that’s what you call

hospitality.

After studying the map we

figured out the easiest route into downtown Mumbai and set off in that

direction. It was a Saturday morning and the roads were surprisingly quiet. We

seemed to have almost all of the highway to ourselves, bar a few cars and

before we knew it we were sitting outside our hotel, wondering what all the

fuss was about. It was only later on that we discovered that motorbikes are

banned from using the elevated Eastern Freeway that we rode in on and that the

fines for doing so can be pretty steep. Luckily for us we weren’t caught and

made it to our destination in record time whilst everyone else battled their

way through the heavy traffic below us.

We chose to pay a few

dollars more than we’d normally pay in order to be in a good location. Mumbai

doesn’t have so many options when it comes to budget accommodation so our $25 a

night room at the Travellers Inn was perfect. Great location, friendly staff and within walking

distance of almost everything we wanted to see as well as being only ten minutes

walk from the central train station. As an added bonus the rooftop area was a

common room where we chatted to some interesting people whilst taking advantage

of the free tea and coffee provided.

That afternoon we got our

first taste of Mumbai traffic, but on three wheels rather than two. We Ola’d a

tuk tuk (India’s version of Uber) to Chor Market, a massive, sprawling area a

lot like the markets in Mexico City where I am sure you can buy anything you

could possibly want. Divided into districts, we wandered through the electrical,

mechanical, car part, tool, fruit and veg sections doing our best to avoid the multitude of scooters and goats also weaving through the chaos. We didn’t really need

anything, but it was fascinating to simply watch people going about their

everyday lives and to observe the tradesmen at work.

When we’d had our fill of

the market, we took a long, slow walk back along Marine Drive towards the Fort

area where we were staying. Along here we found an eclectic mix of people – two

local women in colourful saris on the verge of a fist fight over what appeared

to be a dispute involving one of their daughters and the others son, cops wobbling along the promenade on their push bikes enjoying the sunshine, groups of guys

hanging out and staring as we passed. There was also an edge to the area.

Whilst Evan used a public toilet, I waited outside and had to move away from

where I was standing several times to fend off unwanted attention. One man

wearing grubby clothes fixed me with a sinister grin whilst closely watching my

bag and the camera in my hand as he edged closer along the sea wall. I’m not

one to be easily spooked, but I’ve learnt over the years I’ve travelled alone

to have a good sense of when it’s best to move and avoid a potential situation

and this was one of those times.

Further along the waterfront

we sat for a short while on the wall when Evan pointed out a seedy looking guy

and his friend trying, and failing, to take covert photos of us. Ignoring them at

first, they obviously took this as a cue to up their game and walked towards

us, the seedy looking guy filming with his mobile phone camera pointed directly

at my chest. Evan stood up and stepped in front of me, holding his hand out to

cover the camera lens, telling him angrily ‘No!’ but the guy just grinned, shrugged

and continued to film. To be honest I’m surprised Evan let him walk away

without grabbing his phone and throwing it in the sea, but it was probably for

the best that he didn’t. As far as disputes between locals and tourists go,

we’ve heard plenty of stories and it never ends well for the foreigner

regardless of whose fault the incident was.

After considering a movie,

but discovering that no cinemas have English subtitles we opted instead to

ignore our now sore feet and continue walking towards the Gateway of India, a

large archway, through which the last British troops to leave India passed in

1948. It also sits opposite the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, an impressive building,

infamous for the damage that it sustained in the 2008 Bombay bombings. We

wandered a while watching the hundreds of selfie-takers trying to capture the

perfect shot against the backdrop of a giant moon hanging from a crane before

deciding to take a boat ride from the dock to see what the skyline looked like

from the water. In reality it was a little disappointing. The boat ride

doubled as a water taxi for the various boat operators who were moored in the harbour

to get back to their boats, so at least this provided an interesting peek into

their lives as we watched them prepare their meals and set up their beds.

Most of the time we have no

plans on our trips and read very little about places before we visit so as not

to have preconceptions and expectations. Some of the most memorable things we

have seen and done have stemmed from a chance meeting or recommendation from a

local person or another traveller, but in Mumbai there was one area we had

talked a fair bit about before we arrived - the slums of Dharavi.

I think I must have been one

of only a few people who had not seen Slumdog Millionaire at this point in time,

but I was aware that the second largest slum in Asia and the third largest in

the world was situated in Mumbai and that parts of the movie had been filmed

there. Dharavi is home to around a million people living in extremely close

proximity to each other, often in what we would consider abject squalor and

with extremely poor sanitation. It was a dilemma, deciding whether a visit to

the area was an ethical choice to make. Do these people really need western

tourists gawking at them as they go about their daily lives? I can understand

how visiting such a place could be likened to visiting orphanages and other

such places, ‘poverty tourism’ and voyeurism at its worst, but as I read a

little about the area I came across the website of Inside Mumbai Tours.

Run by a student resident of

Dharavi as a means to fund his education, Mohammad Saddique offers tours of the

slum, the home of his family for more than 50 years, imploring people to put their preconceptions

aside and experience a place that he guarantees will dispel the negative views most people have of a slum. His tours focus on the numerous industries

that operate within the slum – plastic recycling, poppadum making, pottery, leather,

textiles, soap making, electronics recycling and commercial embroidery - and the people that make them happen. A quick

whatsapp message later and we were set to meet our guide, a friend of Mohammad’s

and fellow slum resident, at the nearby train station at 11am the following

morning.

As the train neared Dharavi

the trackside litter increased and the ramshackle corrugated tin buildings

stretched out alongside the tracks. The trains here have no doors so we could

hang out the side as the train moved, taking in the sights, sounds and smells

of our surroundings. At the station we waited by the ticket office as requested

and soon we were joined by Moshin, a business student in his final year of

school. After a short explanation of what we were about to see, a few requests –

please don’t pull faces if there are bad smells, smile and say hello to people

and do not take photos or give anyone money - he led us across the road and into the heart of the

slum.

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

Founded during British

colonial rule over 100 years ago and covering an area of just over two square

kilometres, the slum really is a very unique environment. I had imagined

walking ankle deep in raw sewage and litter, being glared at by residents not

happy with our presence, but the reality could not have been more different.

Much of the area we visited first was little different to any other Indian market

street, albeit with everything more closely crammed together.

We paused outside

a tiny cinema, built to allow the Dharavi residents who cannot afford the 200 rupee

tickets at the commercial cinemas a chance to see movies and sports matches. With

only 20 or so seats at each venue, tickets cost a tenth of the price of a normal

cinema. Apparently, when a big international cricket match is playing the

crowds spill out on to the street, clamoring to get a view. Contrary to popular

belief, the slum has full and legal 24 hour electricity and residents pay bills

for this. It also has its own schools, a university, hospitals and other vital

services.

What is maybe most

extraordinary about Dharavi is that it is home to around 15,000 mini factories,

industries that together turnover in excess of US$665 million a year. Plastic

is brought here from not just Mumbai, but all over Asia to be recycled. Employing

around 250,000 people, the recycling industry in Dharavi is easily its largest

enterprise. Plastic waste is sorted by type, grade and colour before being

thoroughly cleaned, dried on the rooftops and shredded into huge sacks ready

for sale to the manufacturing industry.

At another factory we saw the soap

making process, at yet another biscuits were being made. Here the workers live almost

their entire lives within the bakery, working for more than fifteen hours a day

and then sleeping on the floor where they work. Many of these businesses exist

high above the ground, several stories up. Climbing up a rickety ladder between

some tin sheets we emerged into an embroidery factory where three large computerised looms churned out beautifully stitched textiles for the European market.

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

What struck me most however, as

we made our way through the narrow maze of lanes, often only just wide enough for a person to

squeeze through and not high enough to stand up straight, was the smiles we

received from everyone we passed. Small children beamed and offered their

outstretched hand to shake accompanied with a confident and polite ‘Hello!’

No-one asked us for money or hung off our arm with a pleading look on their

face as we have encountered in so many places. Women cooking in their tiny

kitchens waved and smiled as we passed their doors, the smell of spices and herbs mixing with the inevitable smells from the raw sewage running through the open gullys outside. These people were happy, well fed, employed and their children educated. It was a pleasure to have the chance to

meet them and to see where they live and work.

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

|

| Photo: Inside Mumbai Tours © |

Moshin explained to us that the slum is a unique community when it comes to just about every aspect of life. He told us that residents are free to choose exactly what they want to do with their lives and what they want to believe in, and that all of the major religions in India are represented there and live happily side by side. With a population made up of immigrants from all over the country, a more diverse mix of culture, ethnicity and socio-economic status would be hard to find anywhere else in India. He said it was not unusual to see a group of women sitting chatting of an evening, Muslim, Hindu and Christian together, their differing religious beliefs having no bearing at all on their friendships with each other.

He explained too that there was strong resistance from the slum residents in some areas to plans to raze areas of the slum to the ground and to build brand new tower blocks, each with their own places of worship. This would mean the Christians would be moved into apartments in a block with a church, Hindu’s into one with a temple, etc, a move strongly and understandably opposed by residents who do not wish to move to segregated living. The reality is though that the slum occupies prime building land and prices are startling high, in fact some of the existing tower block apartments in the area command prices similar to those of downtown Manhattan. Mumbai really is a city of extremes. We didn't see it, but the world's most expensive private residential home is located in Mumbai with views over Dharavi. Known as 'Antilia', the 27 storey, 400,000 square foot skyscraper is the home of Indian business tycoon Mukesh Ambani and is valued at in excess of US$1 billion.

As we left Dharavi, we

paused to stand on the pedestrian footbridge that spans one end of the slum.

When we had met him at the train station, Moshin had asked us our opinions

of what we thought a slum was and what we thought we were likely to see. He promised us that when we

left, we would see the place in a very different light and he was absolutely right.

What we witnessed was the power of human spirit to overcome difficult conditions and

create the best possible situation out of what is available. We also saw that,

with the horrendous volume of plastic waste produced in this world, Dharavi is

providing an essential and invaluable service with its plastic recycling

efforts, an industry that receives no government support, but is taxed. What we

experienced in that unique community stayed on my mind for many days afterwards

and I would recommend anyone planning on visiting Mumbai to contact Mohammad and

go experience this extraordinary community for yourself.

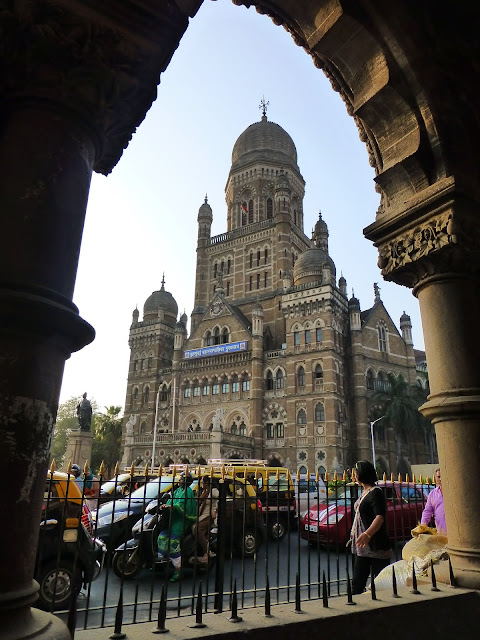

All

in all Mumbai wasn’t at all as I expected it to be. I think I was expecting a

dirty, smelly city, not dissimilar to Chennai, but what we found was a

relatively modern city with some stunning architecture dating back to times of British rule

that looked every bit like it belonged in London. The markets were really the

only part of the city that gave a clue that we were in India, the rest could

have been a dozen other places in the world, yet as a whole it had a flavour all

of its own. The central railway station, formerly known as Victoria Terminus

but now renamed Chatrapati Shivaji Maharj Railway Terminus is a designated

UNESCO site. The Gothic-revival style architecture dominates the area in which

the building sits and is reminiscent of Kings Cross St Pancras. It was also a

victim in the 2008 bomb attacks when two terrorists threw grenades and opened

fire with AK-47 rifles in the main passenger hall killing 58 people and

injuring a further 104. Tours of the majestic building are available on weekday

evenings, but unfortunately we were there at the weekend and sadly had to skip

this.

Feeling the need to be on

the move again, we hopped back on our bikes the following morning and headed

out of town. With our new found knowledge that motorbikes are not allowed on

the freeways, I resisted Evan’s pleading looks and insisted that we follow the

rules and join the trucks on the road below it as we headed north out of town.

Taking us around 2.5 hours rather than the 45 minutes we had taken on the

freeway, we wove our way through the traffic and cows, A.M. 180 playing on loop

in my head. Ok, it’s from Under the Western Freeway, but for some reason my

brain made the connection and wouldn’t let it go.

Mumbai was the first place

we’d been in India that I had truly enjoyed and I was happy to be back on my

bike, excited for the first time to see what was in store for us next.

Disclaimer - the contents of this post are in no way commercially connected to Inside Mumbai Tours, they are my honest opinions based on my experiences in Dharavi and I received no financial reward for what I have written here. The photos above credited to Inside Mumbai Tours were kindly provided by Mohammad Saddique as it was not possible for me to take my own photos inside the slum.

Well there are still ups and downs aren't there. I'm hoping the good times are starting to outweigh the bad by now. You are both so very brave tackling the roads, I really admire you for it. I guess you won't have any desires to visit there again. By the way, have you both lost weight. Thanks for keeping the blog going, it's so interesting. xxx

ReplyDelete